Inflation Yields

This past August, I touted the short-term merits of Series I Inflation Bonds, also known as I bonds. Because the inflation-based yields on I bonds are calculated in arrears, their upcoming 12-month returns can be largely anticipated. From August 2022 through July 2023, I wrote, I bond inflation yields would likely surpass 9%. I somewhat overshot the mark: Their actual return will be 8.21%.

Nevertheless, I bonds were a great one-year investment. Although they carry 30-year maturity dates, I bonds may be sold one year after they are purchased, at the cost of three months’ worth of interest. (The interest penalty vanishes after five years.) Thus, August 2022′s buyers could pocket 8.21% over the next 15 months. At that time, Treasury notes paid an annualized 3.3%. Quite the advantage for I bonds, considering that both securities are backed by the United States government.

The bloom is now off the inflation-yield rose, mostly because of sinking energy costs. I bond inflation yields are derived from the unadjusted version of the Consumer Price Index for all Urban Consumers, or CPI-U. Energy prices buoyed that indicator from spring 2020 through spring 2022, but they are now dragging it down. That’s good news for the public but bad news for I bond owners.

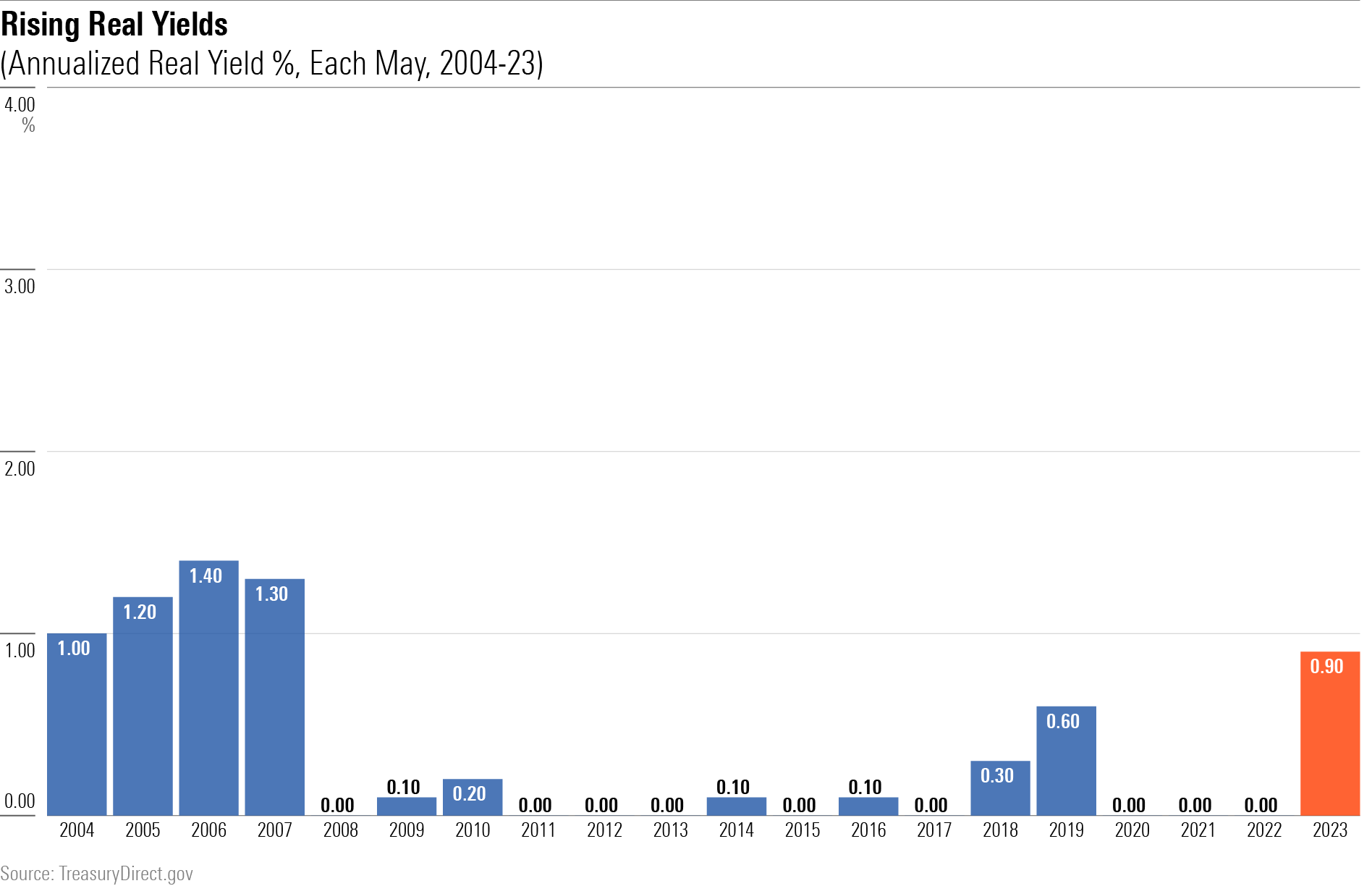

To be sure, I bond inflation yields remain generous by recent standards. The following chart shows the inflation yields for I bonds since 2004. (These figures apply to I bonds purchased from May through October. Those acquired from November through April had different returns. Also, the 2023 figures do not represent an entire year, but instead the annualized rate for the next six months.) Since 2007, the inflation yields on I bonds have rarely outstripped today’s level.

Fixed-Rate Yields

All fine, but that picture scarcely supports my claim of a “fire sale.” Now comes the kicker. Besides the inflation yields, I bonds sometimes provide what the Treasury Department calls a “fixed-rate yield”: a return source that exists in addition to the inflation rate. Whatever happens to consumer prices, the fixed-rate yield persistently supplements the inflation yield. (The only exception is if consumer prices decline. In that case, the fixed-rate yield is used to defray the deflation.) This past Friday, the Treasury announced its upcoming fixed-rate yield: an annualized rate of 0.90%.

That is unusually high. Since the mid- 2000s, the Treasury has only sporadically awarded fixed-rate yields, none of which have reached 0.90%.

The fixed-rate gift is permanent. Whereas inflation yields fluctuate, the fixed-rate yield remains attached to the bond forever. Investors who buy the current vintage of I bond, which runs through the end of October. will receive that 0.90% annual bonus for as long as they own the security. (Well, not quite the end of October, as the Treasury regards Halloween as the first day of November. I bonds are goofy.)

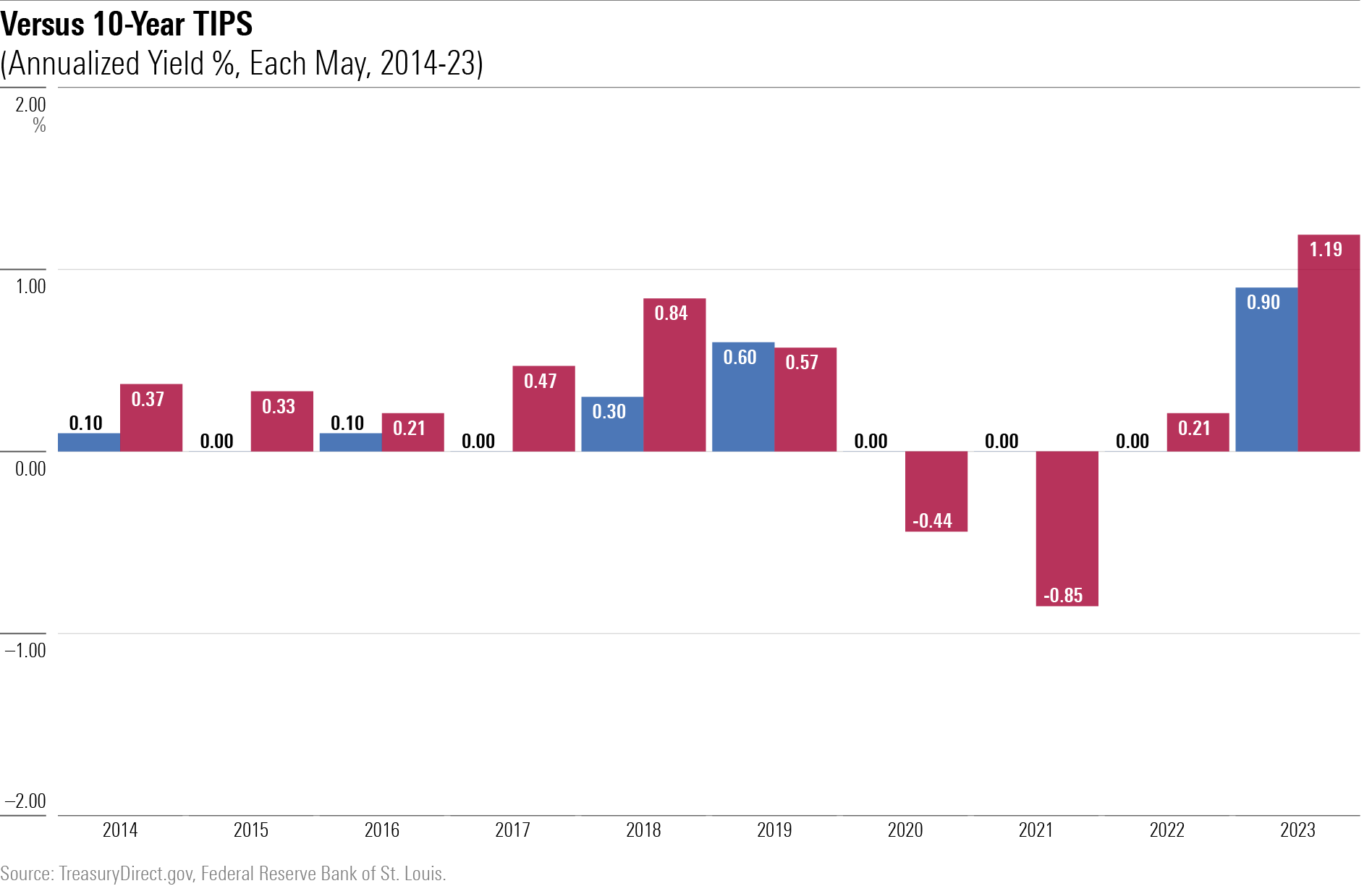

The Treasury does not reveal how it determines the size of the fixed-rate yield. However, its decisions are guided by the prevailing real yields available on Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities. (Fixed-rate yields and real yields are synonymous.) The next exhibit depicts the fixed-rate yields paid by I bonds that were issued in each May over the past decade, shown in blue, along with the concurrent real yields on 10-year TIPS, in maroon. The relationship is visible.

The Long View on I Bonds

The argument for I bonds has been reversed. Last summer, I bonds were certain near-term winners with uncertain future prospects. Today, their primary appeal is for the long rather than short term. Their inflation yields no longer exceed the payouts on one-year Treasuries. (Counting the contribution of the fixed-rate yield, the contest is pretty much a wash.) However, their fixed-rate return is appealing.

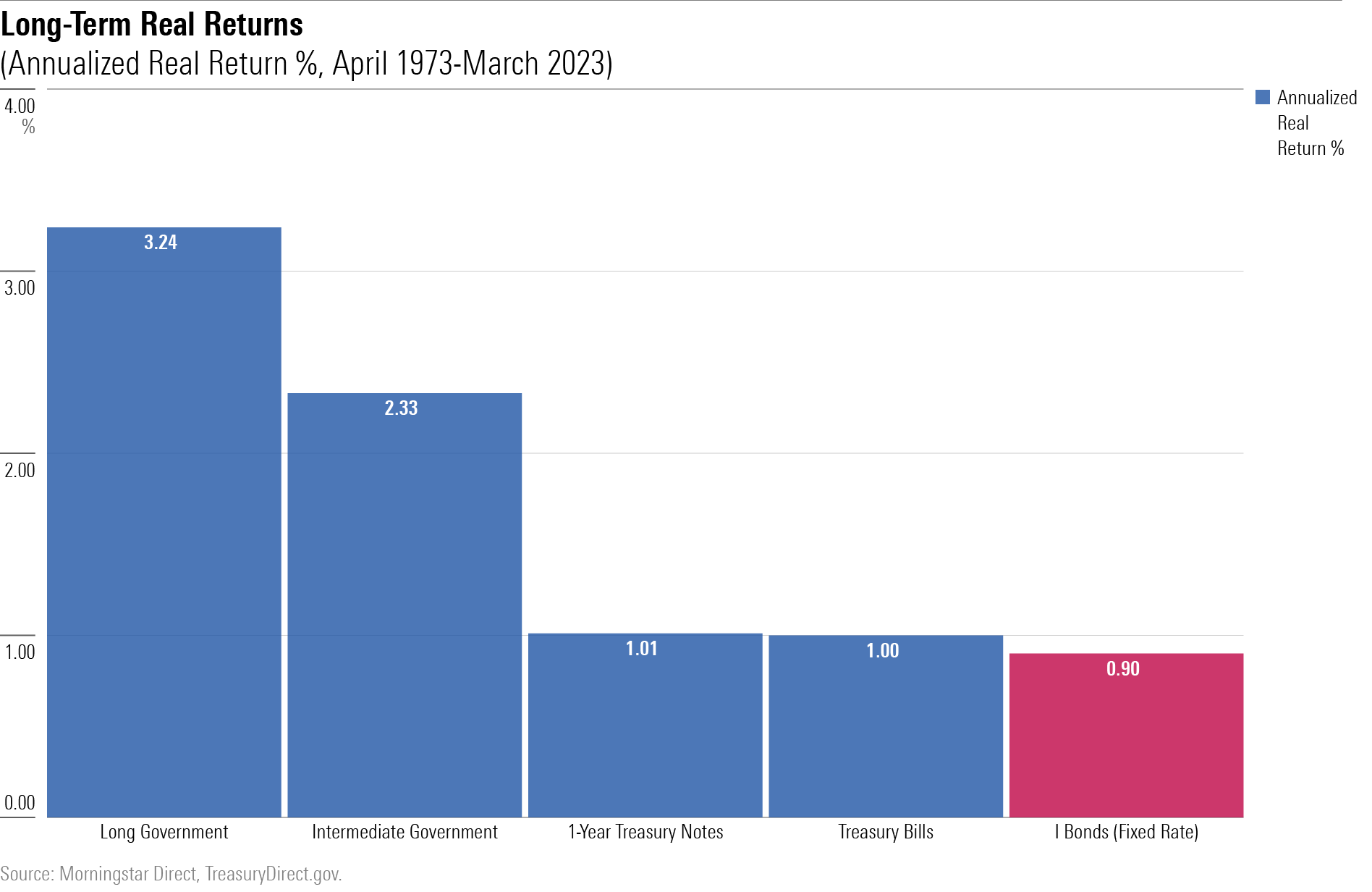

The following chart depicts the average annualized real return achieved over the past half-century for 1) long Treasury bonds, 2) intermediate-term Treasury notes, 3) one-year Treasuries, and 4) Treasury bills, along with the future 0.90% return that today’s I bonds will provide.

Over the very long haul, that 0.90% fixed-rate return is acceptable but not great. It’s pretty much in line with cash and short notes, but well behind intermediate and long Treasuries However, that period contained two notably bad stretches. The first slump occurred during the 1970s, when inflation raged at levels that (thankfully) have yet to be repeated. The second occurred much more recently, over the past decade. When inflation was dormant, so were Treasury yields. And then when inflation suddenly rose, their payouts lagged.

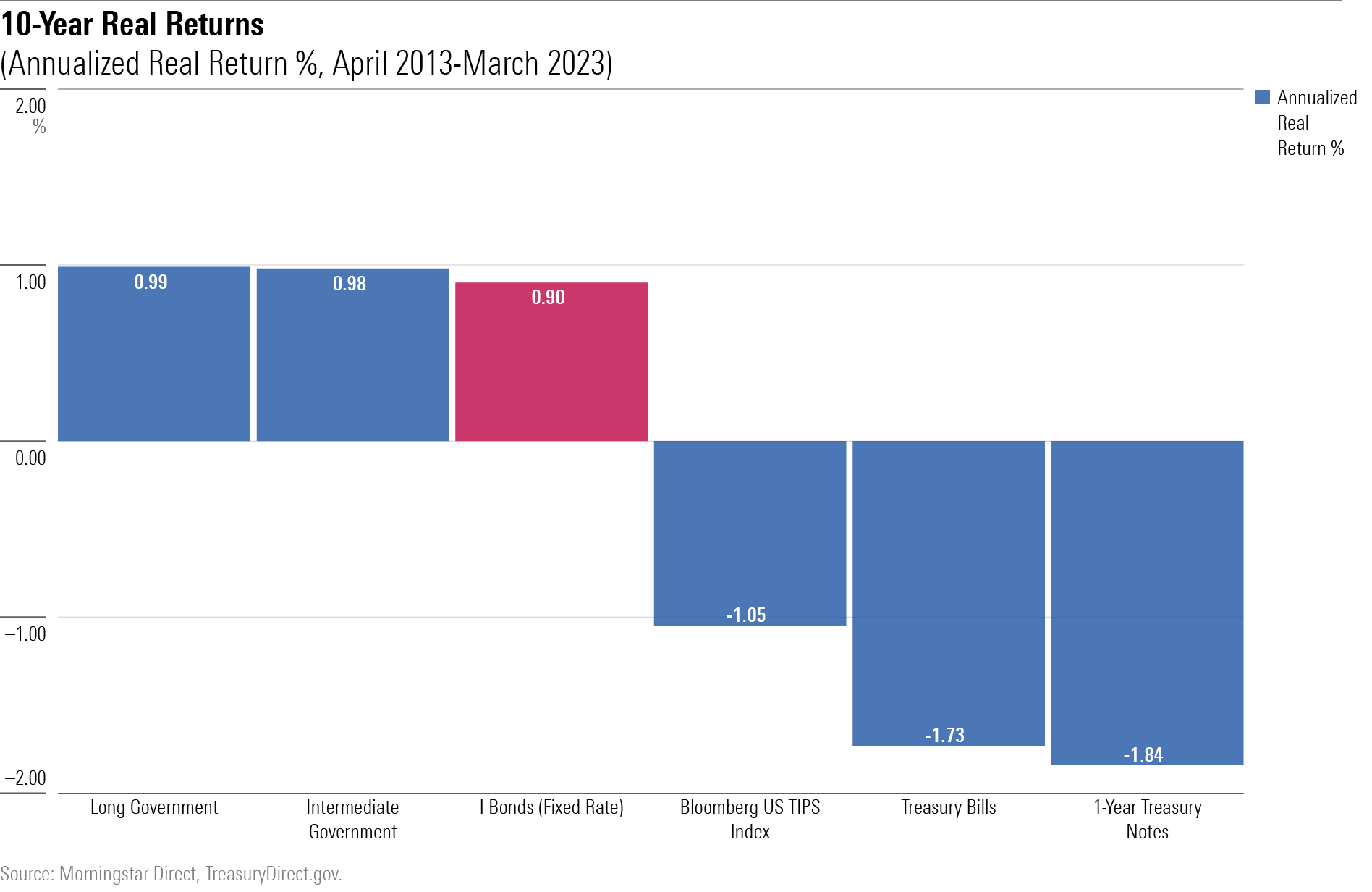

The result was distinctly unpleasant. Long and intermediate-term Treasuries were clobbered in the 1970s. (I omitted showing those results, as I have enough charts already, but the picture is not pretty.) This time around, their term premium enabled them to keep pace with the annualized 0.90% real return that I bonds will deliver in the future, but with far greater volatility. Meanwhile, Treasury bills and one-year notes were left far behind. TIPS also lagged, because (as we have seen) their real yields ballooned. In short, investors forced TIPS to discount their prices.

What’s in Store for I Bonds

Currently, nominal Treasury securities with maturity dates of more than three years yield about 3.6%. Consequently, they will prove superior to I bonds only if the long-term inflation rate is below 2.7%. Can you confidently state that will be so? Even though I am something of inflation optimist, I would not take that gamble.

While one cannot say what cash and one-year Treasuries will bring in, as their yields constantly change, their 50-year results have roughly matched those of I bonds. Two features tilt the scale in favor of I bonds. First, the returns on I bonds are not taxed until they are redeemed. Second, I bonds offer flexibility. If real returns on cash and short Treasuries become unusually high, I bond owners can trade for them. But if real returns on those securities disappear, as occurred during the 2010s, then they can stay ahead of the game by retaining their I bonds.

The toughest competition for I bonds comes from TIPS, which are also attractively priced. However, it’s possible that TIPS could become cheaper yet, thereby extending their current streak of negative real returns. Also, in the unlikely event that deflation strikes, the inflation yields on TIPS will be negative. The Treasury forbids that possibility with I bonds. By construction, the combination of their inflation and fixed-rate yields cannot go below zero.

(To provide the full details: The Treasury will always pay at least the par value for TIPS. Thus, TIPS issued during a deflationary environment will not suffer markdowns. However, seasoned TIPS that have appreciated because their prices have risen in response to inflation will lose value, should deflation strike. The same does not apply to I bonds, as their overall yields are never negative.)

Without question, I bonds have disadvantages. They are subject to a strict purchase limitation ($10,000 per year for each individual, $15,000 if bought with a federal tax refund) and are available only through the TreasuryDirect.gov website. The latter complicates record-keeping by preventing accounts from being fully consolidated. At current prices, though, prospective I bond investors may willingly accept that hassle.

John Rekenthaler ([email protected]) has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar’s investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.